Vote Leave. Take Control?

21 April 2024 06:26 PM

Wasn’t it supposed to be about taking back control? You could say that this over simplifies the many and varied hopes of Leave voters but in 2016 the British electorate had voted to leave the European Union based on the promises of the lead campaign, Vote Leave. The campaign’s key promises resonated strongly with the UK electorate so, and for the sake of this article, we can superimpose these promises as the key causes and issues for the British public. But appending a question mark to the Vote Leave campaign slogan begs the question: What did voters want to take control of, and have they gotten it in the eight years since?

The outcome of the 2016 referendum, concluded more than 40 years of contention within British politics over the European Project. The most divisive of issues circling this debate, was of course, immigration. The ‘Why Vote Leave’ website appealed to their voter base by stating that “We can control immigration”. Research shows, this was a key issue for the majority of voters in 2011; a concern which has been promised to be resolved by every Prime Minister since David Cameron. However, according to the ‘Why Vote Leave’ website, attempts at border control law were being overruled by EU judges.

The sovereign dissonance between the supranational Council of the EU, and the British Parliament was framed by the Vote Leave campaign as the cause of the immigration issue. Voters believed that British People should be making British law.

In an article for The Sun, designed as official campaign material, Boris Johnson claimed that, “[including] both primary and secondary legislation, the EU now generates 60 per cent of all the laws that pass through Westminster. […] We have lost control of our borders to Brussels.” The British public acknowledged that British Laws were being written by European bureaucrats hundreds of miles away, and saw this as the root cause of the failure of successive governments to make good the promises on immigration.

In the same article, Johnson hits on another campaign promise saying, “We have lost control of our trade policy […] This project is a million miles away from the Common Market that we signed up for in 1973.” As Johnson points out this is how the Union started, however since the Maastricht Treaty, EU agreements have very seldom been just economic agreements, they often contain considerable political and military clauses. This drift away from a simple economic project and the potential of that fact to cause constitutional crisis in the UK has historically been acknowledged with figures such as 1998 leader of the opposition William Hague arguing that we ought to be, “In Europe but not run by Europe”. Expressing how those in Britain would like to reap the benefits of being in Europe, of being in the single market, while “rosinenpicken” the rules we would be subject to.

On the economic side of the leave vote, it is a little less clear. Voters wanted tighter controls on the free movement of people across our borders, which meant leaving the Single Market. The Vote Leave website also claimed that, “The EU stops us signing our own trade deals with key allies like Australia or New Zealand, and growing economies like India, China or Brazil.” They argued the UK would have greater flexibility in global trading without the Customs Union.

So, where are we now?

Have we controlled immigration? The British public would argue, no. In voting leave, many were expecting a new “points-based immigration system” and that this would mean lower migration into the UK. Some even thought that it would mean a significant emmigration of Europeans, a net negative migration.

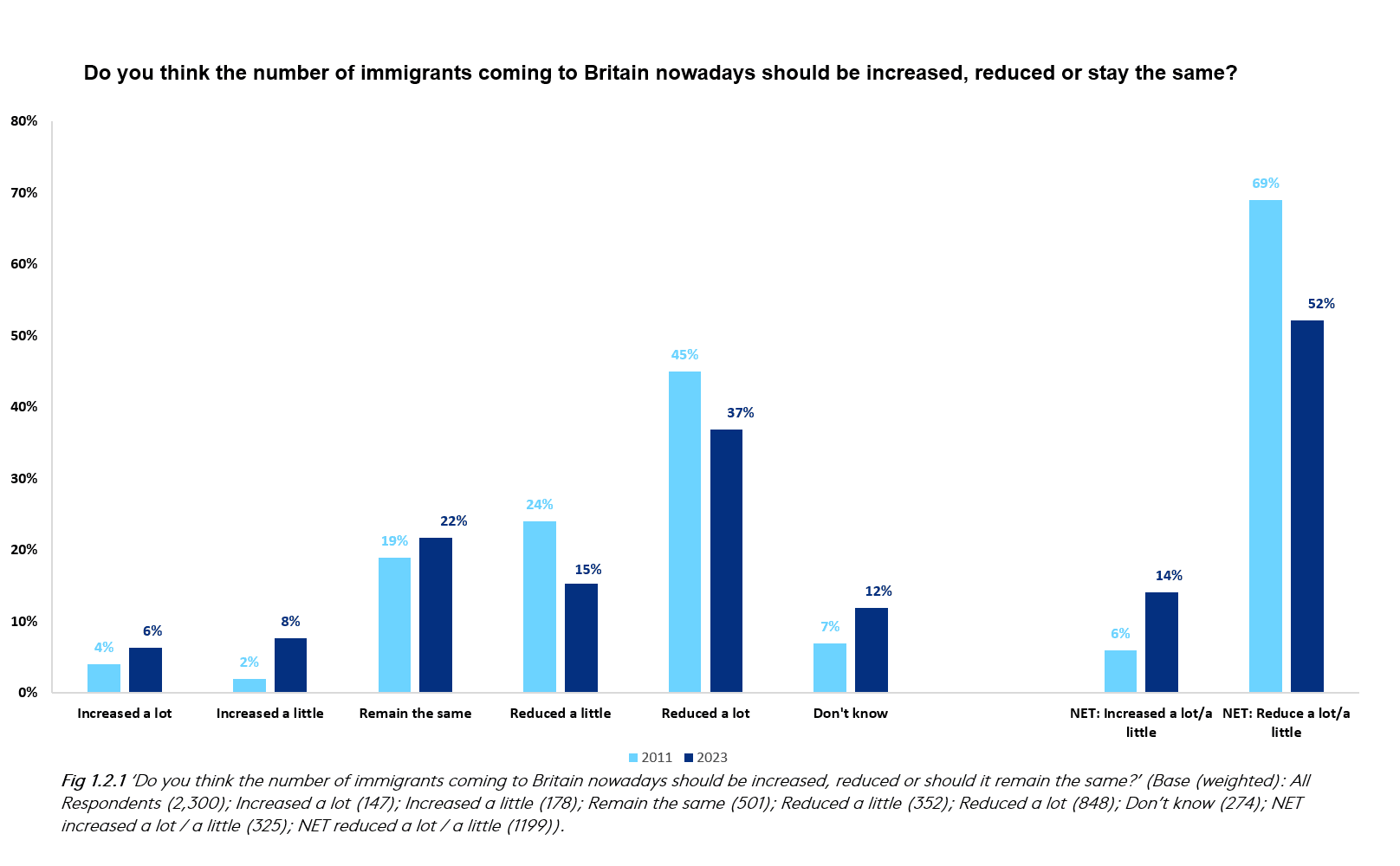

Research in 2023 showed that 52% of respondents thought that immigration needed to come down, 37% said it should be reduced significantly. And when compared with 2011 these numbers haven’t changed significantly (see chart below).

According to Brindle and Sumption (2024), “While EU migration did decline, non-EU [and overall] migration has hit record levels.” They explain the main causes of this drive in non-EU migration as coming from family members of students and workers, humanitarian visa schemes and an increase in work visas for care work and public sector jobs that aren’t subject to the increased £38,700 salary threshold.

Are we benefitting from being able to trade with the whole world? So far, not really. The majority of our trade deals recreate what we had pre-brexit with our closest neighbour, the EU, as part of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in 2021. And whilst the agreement puts no tariffs or quotas on any UK-EU trade, firms have become laden with bureacratic “red tape and regulatory barriers” (Sampson, 2024) if they want to export to the union.

As for the rest of UK trade, deals have been drawn-up and analyses made with Australia, New Zealand and nearly a dozen other countries across the Pacific but they are meagre. Each being expected to contribute no more than 0.1% to GDP by 2035 by the government’s Departments for International Trade, and, Business and Trade.

The pandemic lockdowns obscure the view but two years after, the UK is one of the only major world economies that hasn’t fully recovered. Brexit may be the cause, it’s hard to tell. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, as a result of the TCA, the UK is set to suffer a “[reduction in] long-run productivity by 4 per cent relative to remaining in the EU.” Implying that, despite covid, Brexit has had a negative effect on the UK economy. In his chapter ‘Trade’ for the UKICE’s 2024 report on the UK economy, Sampson outlines that UK has had the weakest growth in goods exports and imports of the G7 and that this is caused by the barriers caused by the TCA.

For now, the country is waiting on elusive deals with major economies like China, India and the United States. If these come to fruition the economy might see the long-term boons promised by the Vote Leave campaign. But for the time being, the UK is unfortunately stagnating without the European Union.